Gregory of Nazianzen represents a viable alternative to the allegedly heterodox notion of the atonement represented by reformed theologians such as Keller. The Father did not forsake Christ, but Christ cried out on part of humanity on the cross.

What did it mean when Christ on the cross cried: “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?“, “My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me?” (Matt. 27:46). Was Christ really forsaken by God?, did he just quote Psalm 22 in order to imply its optimistic ending?, or did he perhaps in his human nature experience godforsakenness while still being one with his Father in his divine nature?

A popular notion in Protestantism is the idea that Christ dies as a substitute for sinners, receiving the just punishment of sin as the Father turns his back on him, forsaking him at the cross. Critics of the traditional Protestant notions of the atonement, however, often accuse this idea for implying a breach in the trinity. If the Father can turn away from Christ, then Christ cannot be substantially one with the Father.

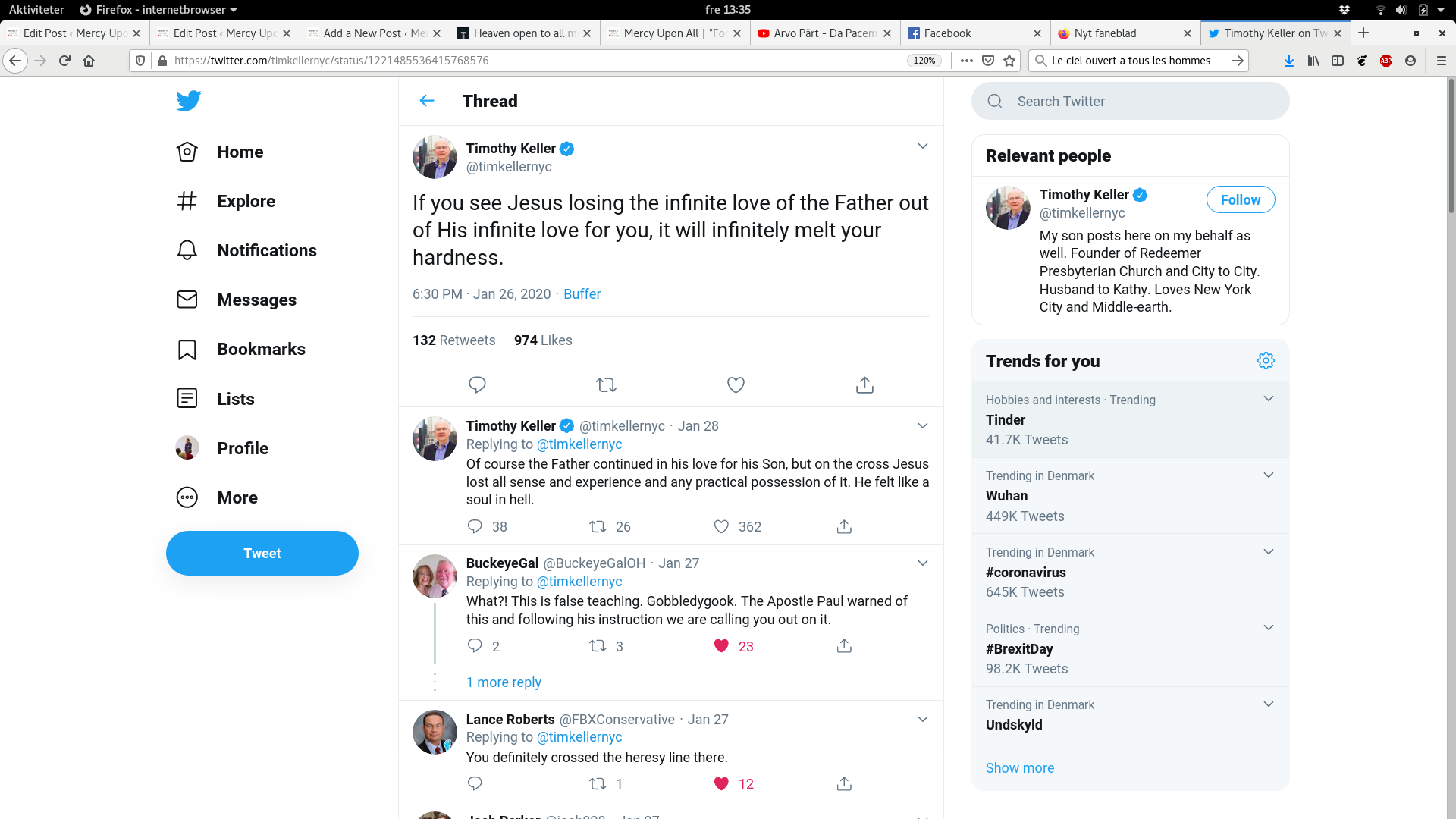

An example that the traditional Protestant notion of the atonement can at least be interpreted as verging on non-trinitarian heterodoxy, could be observed as the popular Presbyterian pastor Timothy Keller recently made a post on Twitter. In his post Keller seemed to be saying that Jesus actually lost the love of his Father on the cross:

There were plenty of reactions accusing Keller of heresy. If Christ could loose the love of the Father, this would in effect imply that the trinity ceased to exist, making God nothing on the cross. Keller has explained elsewhere, that his view is more precisely that of Calvin’s, where Christ is only said to experience the loss of the Father’s love, even if there is not an ontological breach in the trinity.

But what are the alternatives? Shortly after reading Keller’s tweet, I ran across a passage in the 4th century Cappadocian theologian Gregory of Nazianzen. Gregory presents the idea that Christ in himself subjects all humanity to the Father, thereby becoming the representative of humanity before God. When Christ cries “Why hast thou forsaken me?” it is sinful humanity that speaks through Christ, but the Father did not, for this reason, forsake Christ:

“[T]he Son subjects all to the Father […] And thus He Who subjects presents to God that which he has subjected, making our condition His own. Of the same kind, it appears to me, is the expression, “My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me?” It was not He who was forsaken either by the Father, or by His own Godhead, as some have thought, as if It were afraid of the Passion, and therefore withdrew Itself from Him in His Sufferings (for who compelled Him either to be born on earth at all, or to be lifted up on the Cross?) But as I said, He was in His own Person representing us. For we were the forsaken and despised before, but now by the Sufferings of Him Who could not suffer, we were taken up and saved. Similarly, He makes His own our folly and our transgressions; and says what follows in the Psalm, for it is very evident that the Twenty-first Psalm refers to Christ.” (Gregory of Nazianzen, Fourth Theological Oration (Oration 30), V)

I find Gregory’s solution brilliant in its simplicity and its clear affirmation of the Patristic understanding of Christ’s incarnation as a union with humanity as such. Humanity has turned away from God and thus experiences godforsakenness. It is this experience that is expressed at the cross, even while Christ is still fully one with the Father. Notice also, that Gregory is quite explicit in saying that, paradoxically, God did actually suffer, even if he cannot suffer. But for this exact reason, as Christ makes our godforsakenness his own on the cross, we also get to share in his affinity with God in the resurrection. In this way, there is no breach of the trinity on the cross, but only a participation of Christ in human suffering (rather than Christ being a “substitute”) and a subsequent human participation in Christ in the resurrection. I’m not sure that this is actually very far from Keller’s view, but I’m quite sure that I prefer Gregory’s formulation over Keller’s.