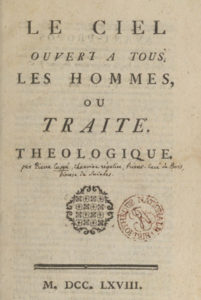

I recently came across a peculiar book by Pierre Cuppe, a French 18th century pastor. The English title is “Heaven Open to All Men” (“Le ciel ouvert a tous les hommes” in French). I have not been able to find much information on its author, but the English translation of his book is available online. The title may initially seem to suggest a somewhat Arminian argument or a similar notion of general redemption, but the subtitle makes it clear that not only is heaven open to all, but in fact all will eventually be saved.

The full title of the 1743 edition was “Heaven open to all men or, a theological treatise, in which, without unsettling the practice of religion, is solidly prov’d, by scripture and reason, that all men shall be saved, or, made finally happy.”

The full title of the 1766 edition (which I refer to below) was: “Heaven Open to All or, Universal Redemption Asserted and vindicated from Scripture, the Attributes of the Deity, and the Reason and Nature of Things: Designed to Explode those narrow Principles which some have inculcated, And to excite a general Piety and Charity amongst Mankind”.

Cuppe’s arguments

Central to Cuppe’s argument is the distinction between the “earthly man”, Adam, and “the heavenly man”, Christ. Both represent humanity in its entirety. Antichrist is nothing but humanity considered in its sinful state without God. Every human person, considered as the offspring of Adam can be called the “Antichrist”, Cuppe explains. But considered in the light of the redeemer every human person is the new man, reconciled to God (p. 18). In other words, God represents humanity in “two very different lights”, as odious, considered under the power of the old man”, and as reconciled, considered as justified by the grace of redemption.

In this way Cuppe can indeed envision the perdition of the sinner, i.e. humanity in its entirety as it is without God, while simultaneously maintaining that all human beings will be saved eventually. Antichrist is forever excluded from the “divine favour”, but being reconciled to God through Christ all human beings will be saved.

Cuppe strongly affirms that human beings are justified by Christ alone. Though not using the concept explicitly, Cuppe in a passage even seems to advocate the idea of justification from eternity, prominent among some radical reformed theologians of his time. It is not our subjective faith or “acceptation” of Christ that restores us, but Christ’s eternal acceptence of us. Christ is from eternity the “mystical Lamb” that restores humanity “by anticipation” (of the cross, I assume). In this way Cuppe seems close to Jeremiah White‘s idea, that all of humanity is, in fact, saved from eternity.

“Adam’s acceptation of the coming of the Redeemer was not that which restored him. It was the acceptation by the mystical Lamb, immolated from the beginning of the world, the eternal word, who freely taking upon himself the sin of Adam, and, by anticipation, all the sins of men, offered himself to restore them, as a victim worthy to satisfy the Divine Justice for all.” (Pierre Cuppe, Heaven Open to All Men, p. 26)

A second perhaps more idiosyncratic feature of Cuppe’s argument is his distinction between “the grace of redemption” and “the grace of superabundance”. According to Cuppe, the difference between those who have faith here and now, and those who do not have faith, is that, while all are saved, only those who trust in Christ now will have life in “superabundance” after the resurrection. This distinction allows Cuppe to insist that while salvation is of grace alone, nevertheless our faith as well as works does make a difference. There are two kinds of grace, says Cuppe, “the grace of redemption, common to all men”, and “the grace of superabundance, to be obtained in pursuit of means”. The former is common to all, by virtue of the divine promise, while the latter is “proportioned to the right use made of spiritual blessings” (p. 22). Temporal punishments are incurred to the degree that the grace of superabundance is neglected.

I find it hard to square Cuppe’s distinction between two classes of saved (those who are saved through the grace of redemption, and those who are also saved through the grace of superabundance) with the Pauline notion of God finally being “all in all” (1 Cor 15:28) (how can there be distinctions then?). But considering the temporal distinction between “sinners” and “righteous”, I find Cuppe’s approach helpful in making sense of the many passages in the New Testament that seems to suggest that some are saved through faith as well as works, while some are saved as “through fire” (e.g. 1 Cor 3:15).

Download the book here: Pierre Cuppe – Heaven Open to All Men (pdf)