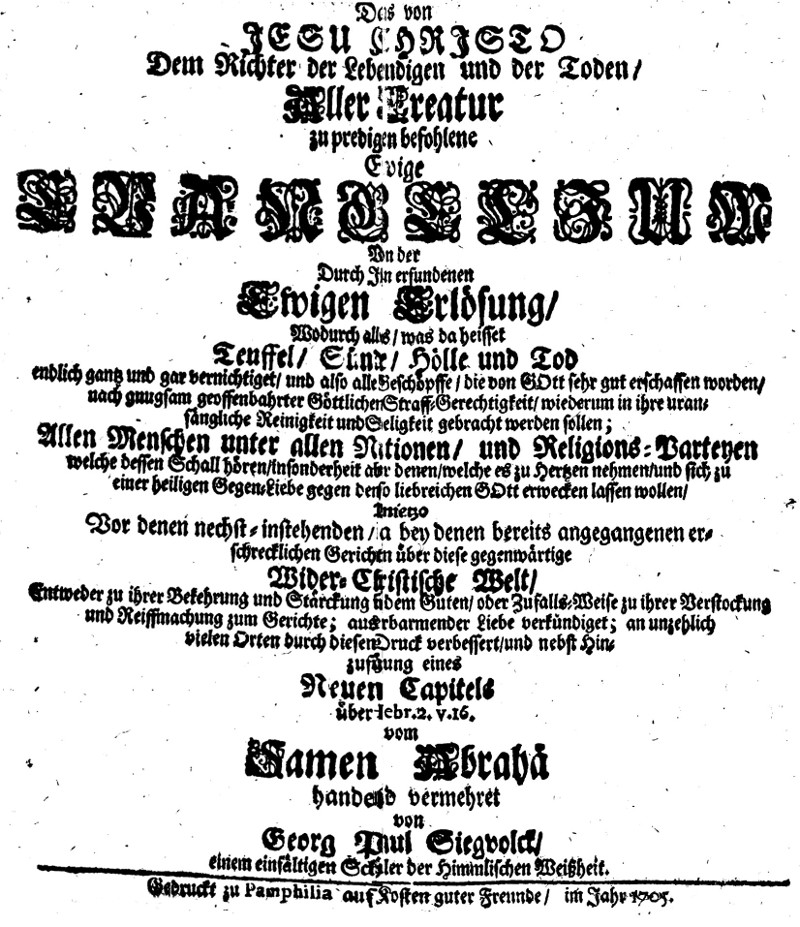

The Everlasting Gospel was written by the German pastor Georg Klein-Nicolai (1671-1734) (sometimes spelled Klein-Nikolai) of Friessdorf, and published under the pseudonym “Paul Siegvolck” in 1705. The German title was Das von Jesu Christo dem Richter der Lebendigen und der Todten, aller Creatur zu predigen befohlene ewige Evangelium, etc. The English translation was first published by Christopher Sower in Germantown in 1753. It was later published by Elhanan Winchester in London in 1792. It is this edition which is here republished in a slightly updated version.

We do not know much about Georg Klein-Nicolai, but he seems (according to McClintock and Strong 1985) to have been an associate of the radical pietist Johann Wilhelm Petersen, a German-Danish theologian, mystic and pastor at the Lutheran Church in Hanover, and later superintendent in Lübeck and Aue. Together with his wife Johanna Eleonora, Petersen developed a mystic and chiliastic form of pietism in which the belief in universal restoration came to play a central role.1 Georg Klein-Nicolai’s The Everlasting Gospel appeared in the first volume of Petersen’s work.2

Another source of influence may have been the Schwarzenau Brethren, a radical pietistic group of German Baptists also known as the Neue Täufer or the Tunkers. The Everlasting Gospel expresses a theological conviction widespread among the Schwarzenau Brethren. Many early Schwarzenau Brethren accepted the doctrine of universal restoration, claiming that after the judgment and punishment described in the New Testament, God’s love would eventually restore all souls to God.

The leader of the Schwarzenau Brethren, Alexander Mack (1679-1735), seems to have believed that after the collapse of several eternities or aeons there would be a final and universal restoration of all things, in which the godless through Christ would finally be saved from their torments in hell.3 Mack believed that the punishments described in the New Testament was of temporary duration, but nevertheless of a severe character. Though the doctrine of eternal torment is not supported by scripture, Mack warned that it is much preferable to put one’s hope in Christ rather than in the belief that there will be an end to punishments. The belief that God would in the end restore all creation through Christ should not be taken as an excuse for sin. Following Mack, the Brethren often kept their teachings to themselves, and they were largely abandoned by the end of the 19th century.

In The Everlasting Gospel Georg Klein-Nicolai expressed beliefs similar to that of Mack’s. Georg Klein-Nicolai does not, however, seem to have merely accepted soteriological universalism as an esoteric doctrine. Rather, the doctrine was something that was to be widely evangelized, while the teachings opposing the doctrine were considered diabolical.

The arguments put forth in The Everlasting Gospel are strongly Biblical and follows the strain of thought recognizable in authors from the Early Church such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen and Gregory of Nyssa, who saw other-wordly torments as temporary and intended for the restitution of the sinner. As such, The Everlasting Gospel remains an important and relevant historical witness to the development, influence and reception of the classical Christian doctrine of the restoration (or restitution) of all things (or in Greek apokatastasis panton). Even if The Everlasting Gospel is not free from errors, and even if the reader cannot follow the author in all of his sometimes extreme conclusions, as when he claims that also the Devil will finally be restored, the book contains many enlightening passages and useful arguments.

Though many of Klein-Nicolai’s claims may seem extreme and unwarranted, his work is a fascinating look into an important part of the history of theological doctrines. Georg Klein-Nicolai seems to have been in no doubt that it is the will of God to restore all fallen creatures. God will attain this purpose, even if the creatures resist him. The belief that creatures are in all eternity capable of resisting God makes creatures stronger than God and thus opens the way to all kinds of “iniquity and atheistic mockery”, says Klein-Nicolai. It is only with God’s permission that creatures are allowed to resist God. The purpose is, says Klein-Nicolai, that the creatures, who will not voluntarily choose the salvation and well-being offered to them, may taste of the bitter fruits of their disobedience. As a result, the rebellious creatures will finally be conquered and thus give themselves up to their Creator, who is able to subdue all. All punishments are, in the end, redemptive.

Though there are minor examples of speculative theology, such as the reasoning that “since God cannot hate himself, he cannot hate his creatures”, the conclusions arrived at by Klein-Nicolai are in most instances backed up by biblical references. This is at least true for the most central claims about the will and capability of God in saving human beings. Klein-Nicolai’s Biblicism seems to revolve around the belief, that it is only by introducing speculative elements and beliefs foreign to the Bible, that one’s conceptions of God’s love become partial and half-hearted. This is not least true for traditional versions of the doctrine of “double outcome”, the belief that Jesus Christ will in the end only save a minor part of humankind. In defense of this idea has since the early Middle Ages been claimed the existence of “two wills” in God, a “hidden God” behind the God revealed in Christ, the existence of a human “free will” making human beings capable of resisting grace, a “double predestination” and so on. Such claims was necessary for explaining why the work of Jesus Christ does only justify and save a few, despite clear scriptural passages such as Rom. 5:18-19. When 1 Tim. 2:3-4 claims that God wants all people to be saved, the traditional argument, repeated by such central protestant figures as Martin Luther, was that God is not bound by his word, and that biblical passages such as these can not be taken at face value, since they are only true of the revealed God.

The author of The Everlasting Gospel makes no such speculative claims. Georg Klein-Nicolai’s theology is firmly grounded in the biblical belief that God is love, that all his attributes, such as holiness and righteousness proceeds from this love, and that no created being is capable of resisting the will of God in the end. Rather than introducing foreign elements in his theology, Georg Klein-Nicolai shows how seemingly contradictory claims about God’s love and willingness to save all on the one hand, and claims about eternal punishment and damnation on the other, can in fact be reconciled on a biblical basis, without making too many speculative claims about the nature of God or human beings.

The most important argument in the book is perhaps the fact that the biblical concept of “eternity” does in most cases not mean “everlasting” in the sense of endless duration. That the original Hebrew and especially Greek words translated as “eternal” does not mean “endless” and, but “age-enduring”, though most Bible translations ignore this fact due to traditionalism, is well-known by biblical scholars.4

There is also the ecumenical aspect. Klein-Nicolai saw the doctrine of universal salvation as having a reconciliatory potential between conflicting opinions on the freedom of the human will. As he says, his doctrine shows the right foundation of divine election and eternal reprobation, and demonstrates both to Lutherans and Calvinists as well wherein each party is right, as what they want. Lutheran Orthodoxy is correct in claiming that God wills the salvation of all human beings and that he saves all who in this life come to faith in Christ. Likewise the Calvinists are right in teaching that all who God wills to be saved shall actually be saved. Those whom God will have to be saved, will actually be saved. God plainly declares in his word, that he will have all men to be saved. Therefore all men will be really saved at last. Klein-Nicolai adds that the doctrine of universal restoration is also capable of deciding the dispute with the Roman Catholics about purgatory. It was not least this ecumenical potential that inspired readers of the book as it was translated into English.

Brought by immigrants across the Atlantic the Everlasting Gospel landed on American soil, where its teachings gained influence as universalism became widespread in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially through the ministry of Elhanan Winchester who released an edition of the book in English in 1792. Elhanan Winchester (1751-1797) was a Baptist preacher and a co-founder of the United States General Convention of Universalists and the Society of Universal Baptists. Inspired by the teachings of the Everlasting Gospel, Winchester believed that God’s love would finally restore everything to its proper place, and argued that the two dominant theological positions of protestantism, Armenianism and Calvinism, in combination lead to the belief that God is both capable and willing of saving all.

Find the book here: The Everlasting Gospel

1Johann Wilhelm Petersen, Mystērion Apokatastaseōs Pantōn, Oder Das Geheimniß Der Wiederbringung aller Dinge, Durch Jesum Christum (1700).

2John McClintock & James Strong, Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature , Volume 10 (1895), pp. 109-33.

3Alexander Mack, Rights and Ordinances; trans. H. R. Holsinger, History of the Tunkers and the Brethren Church (Oakland, Cal.: Pacific Press Publishing Co., 1901), pp. 113-115.

4Ramelli & Konstan, Terms for Eternity: Aiônios and Aïdios in Classical and Christian Texts (Gorgias Press 2007).