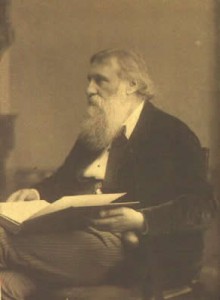

George MacDonald (1824–1905) was a Scottish author, poet, and Congregationalist minister. He was a pioneer in the field of fantasy literature and the mentor of Lewis Carroll and C.S. Lewis. The following is a sermon from Unspoken Sermons (1867).

Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.

– Matthew 22:39.

The original here quoted by our Lord is to be found in the words of God to Moses, (Leviticus 19:18) “Thou shalt not avenge, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself: I am the Lord” Our Lord never thought of being original. The older the saying the better, if it utters the truth he wants to utter. In him it becomes fact: The Word was made flesh. And so, in the wondrous meeting of extremes, the words he spoke were no more words, but spirit and life.

The same words are twice quoted by St Paul, and once by St James, always in a similar mode: Love they represent as the fulfilling of the law.

Is the converse true then? Is the fulfilling of the law love? The apostle Paul says: “Love worketh no ill to his neighbour, therefore love is the fulfilling of the law.” Does it follow that working no ill is love? Love will fulfil the law: will the law fulfil love? No, verily. If a man keeps the law, I know he is a lover of his neighbour. But he is not a lover because he keeps the law: he keeps the law because he is a lover. No heart will be content with the law for love. The law cannot fulfil love.

“But, at least, the law will be able to fulfil itself, though it reaches not to love.”

I do not believe it. I am certain that it is impossible to keep the law towards one’s neighbour except one loves him. The law itself is infinite, reaching to such delicacies of action, that the man who tries most will be the man most aware of defeat. We are not made for law, but for love. Love is law, because it is infinitely more than law. It is of an altogether higher region than law–is, in fact, the creator of law. Had it not been for love, not one of the shall-nots of the law would have been uttered. True, once uttered, they shew themselves in the form of justice, yea, even in the inferior and worldly forms of prudence and self-preservation; but it was love that spoke them first. Were there no love in us, what sense of justice could we have? Would not each be filled with the sense of his own wants, and be for ever tearing to himself? I do not say it is conscious love that breeds justice, but I do say that without love in our nature justice would never be born. For I do not call that justice which consists only in a sense of our own rights. True, there are poor and withered forms of love which are immeasurably below justice now; but even now they are of speechless worth, for they will grow into that which will supersede, because it will necessitate, justice.

Of what use then is the law? To lead us to Christ, the Truth,–to waken in our minds a sense of what our deepest nature, the presence, namely, of God in us, requires of us,–to let us know, in part by failure, that the purest effort of will of which we are capable cannot lift us up even to the abstaining from wrong to our neighbour. What man, for instance, who loves not his neighbour and yet wishes to keep the law, will dare be confident that never by word, look, tone, gesture, silence, will he bear false witness against that neighbour? What man can judge his neighbour aright save him whose love makes him refuse to judge him? Therefore are we told to love, and not judge. It is the sole justice of which we are capable, and that perfected will comprise all justice. Nay more, to refuse our neighbour love, is to do him the greatest wrong. But of this afterwards. In order to fulfil the commonest law, I repeat, we must rise into a loftier region altogether, a region that is above law, because it is spirit and life and makes the law: in order to keep the law towards our neighbour, we must love our neighbour. We are not made for law, but for grace–or for faith, to use another word so much misused. We are made on too large a scale altogether to have any pure relation to mere justice, if indeed we can say there is such a thing. It is but an abstract idea which, in reality, will not be abstracted. The law comes to make us long for the needful grace,–that is, for the divine condition, in which love is all, for God is Love.

Though the fulfilling of the law is the practical form love will take, and the neglect of it is the conviction of lovelessness; though it is the mode in which a man’s will must begin at once to be love to his neighbour, yet, that our Lord meant by the love of our neighbour; not the fulfilling of the law towards him, but that condition of being which results in the fulfilling of the law and more, is sufficiently clear from his story of the good Samaritan. “Who is my neighbour?” said the lawyer. And the Lord taught him that every one to whom he could be or for whom he could do anything was his neighbour, therefore, that each of the race, as he comes within the touch of one tentacle of our nature, is our neighbour. Which of the inhibitions of the law is illustrated in the tale? Not one. The love that is more than law, and renders its breach impossible, lives in the endless story, coming out in active kindness, that is, the recognition of kin, of kind, of nighness, of neighbourhood; yea, in tenderness and loving-kindness– the Samaritan-heart akin to the Jew-heart, the Samaritan hands neighbours to the Jewish wounds.

Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

So direct and complete is this parable of our Lord, that one becomes almost ashamed of further talk about it. Suppose a man of the company had put the same question to our Lord that we have been considering, had said, “But I may keep the law and yet not love my neighbour,” would he not have returned: “Keep thou the law thus, not in the letter, but in the spirit, that is, in the truth of action, and thou wilt soon find, O Jew, that thou lovest thy Samaritan”? And yet, when thoughts and questions arise in our minds, he desires that we should follow them. He will not check us with a word of heavenly wisdom scornfully uttered. He knows that not even his words will apply to every question of the willing soul; and we know that his spirit will reply. When we want to know more, that more will be there for us. Not every man, for instance, finds his neighbour in need of help, and he would gladly hasten the slow results of opportunity by true thinking. Thus would we be ready for further teaching from that Spirit who is the Lord.

“But how,” says a man, who is willing to recognize the universal neighbourhead, but finds himself unable to fulfil the bare law towards the woman even whom he loves best,–“How am I then to rise into that higher region, that empyrean of love?” And, beginning straightway to try to love his neighbour, he finds that the empyrean of which he spoke is no more to be reached in itself than the law was to be reached in itself. As he cannot keep the law without first rising into the love of his neighbour, so he cannot love his neighbour without first rising higher still. The whole system of the universe works upon this law–the driving of things upward towards the centre. The man who will love his neighbour can do so by no immediately operative exercise of the will. It is the man fulfilled of God from whom he came and by whom he is, who alone can as himself love his neighbour who came from God too and is by God too. The mystery of individuality and consequent relation is deep as the beginnings of humanity, and the questions thence arising can be solved only by him who has, practically, at least, solved the holy necessities resulting from his origin. In God alone can man meet man. In him alone the converging lines of existence touch and cross not. When the mind of Christ, the life of the Head, courses through that atom which the man is of the slowly revivifying body, when he is alive too, then the love of the brothers is there as conscious life. From Christ through the neighbours comes the life that makes him a part of the body.

It is possible to love our neighbour as ourselves. Our Lord never spoke hyperbolically, although, indeed, that is the supposition on which many unconsciously interpret his words, in order to be able to persuade themselves that they believe them. We may see that it is possible before we attain to it; for our perceptions of truth are always in advance of our condition. True, no man can see it perfectly until he is it; but we must see it, that we may be it. A man who knows that he does not yet love his neighbour as himself may believe in such a condition, may even see that there is no other goal of human perfection, nothing else to which the universe is speeding, propelled by the Father’s will. Let him labour on, and not faint at the thought that God’s day is a thousand years: his millennium is likewise one day–yea, this day, for we have him, The Love, in us, working even now the far end.

But while it is true that only when a man loves God with all his heart, will he love his neighbour as himself, yet there are mingled processes in the attainment of this final result. Let us try to aid such operation of truth by looking farther. Let us suppose that the man who believes our Lord both meant what he said, and knew the truth of the matter, proceeds to endeavour obedience in this of loving his neighbour as himself. He begins to think about his neighbours generally, and he tries to feel love towards them. He finds at once that they begin to classify themselves. With some he feels no difficulty, for he loves them already, not indeed because they are, but because they have, by friendly qualities, by showing themselves lovable, that is loving, already, moved his feelings as the wind moves the waters, that is without any self-generated action on his part. And he feels that this is nothing much to the point; though, of course, he would be farther from the desired end if he had none such to love, and farther still if he loved none such. He recalls the words of our Lord, “If ye love them which love you, what reward have ye?” and his mind fixes upon–let us say–one of a second class, and he tries to love him. The man is no enemy–we have not come to that class of neighbours yet–but he is dull, uninteresting–in a negative way, he thinks, unlovable. What is he to do with him? With all his effort, he finds the goal as far off as ever.

Naturally, in his failure, the question arises, “Is it my duty to love him who is unlovable?”

Certainly not, if he is unlovable. But that is a begging of the question.

Thereupon the man falls back on the primary foundation of things, and asks–

“How, then, is the man to be loved by me? Why should I love my neighbour as myself?”

We must not answer “Because the Lord says so.” It is because the Lord says so that the man is inquiring after some help to obey. No man can love his neighbour merely because the Lord says so. The Lord says so because it is right and necessary and natural, and the man wants to feel it thus right and necessary and natural. Although the Lord would be pleased with any man for doing a thing because he said it, he would show his pleasure by making the man more and more dissatisfied until he knew why the Lord had said it. He would make him see that he could not in the deepest sense–in the way the Lord loves–obey any command until he saw the reasonableness of it. Observe I do not say the man ought to put off obeying the command until he see its reasonableness: that is another thing quite, and does not lie in the scope of my present supposition. It is a beautiful thing to obey the rightful source of a command: it is a more beautiful thing to worship the radiant source of our light, and it is for the sake of obedient vision that our Lord commands us. For then our heart meets his: we see God.

Let me represent in the form of a conversation what might pass in the man’s mind on the opposing sides of the question.–“Why should I love my neighbour?”

“He is the same as I, and therefore I ought to love him.”

“Why? I am I. He is he.”

“He has the same thoughts, feelings, hopes, sorrows, joys, as I.”

“Yes; but why should I love him for that? He must mind his, I can only do with mine.”

“He has the same consciousness as I have. As things look to me, so things look to him.”

“Yes; but I cannot get into his consciousness, nor he into mine. I feel myself, I do not feel him. My life flows through my veins, not through his. The world shines into my consciousness, and I am not conscious of his consciousness. I wish I could love him, but I do not see why. I am an individual; he is an individual. My self must be closer to me than he can be. Two bodies keep me apart from his self. I am isolated with myself.”

Now, here lies the mistake at last. While the thinker supposes a duality in himself which does not exist, he falsely judges the individuality a separation. On the contrary, it is the sole possibility and very bond of love. Otherness is the essential ground of affection. But in spiritual things, such a unity is pre-supposed in the very contemplation of them by the spirit of man, that wherever anything does not exist that ought to be there, the space it ought to occupy, even if but a blank, assumes the appearance of a separating gulf. The negative looks a positive. Where a man does not love, the not-loving must seem rational. For no one loves because he sees why, but because he loves. No human reason can he given for the highest necessity of divinely created existence. For reasons are always from above downwards. A man must just feel this necessity, and then questioning is over. It justifies itself. But he who has not felt has it not to argue about. He has but its phantom, which he created himself in a vain effort to understand, and which he supposes to be it. Love cannot be argued about in its absence, for there is no reflex, no symbol of it near enough to the fact of it, to admit of just treatment by the algebra of the reason or imagination. Indeed, the very talking about it raises a mist between the mind and the vision of it. But let a man once love, and all those difficulties which appeared opposed to love, will just be so many arguments for loving.

Let a man once find another who has fallen among thieves; let him be a neighbour to him, pouring oil and wine into his wounds, and binding them up, and setting him on his own beast, and paying for him at the inn; let him do all this merely from a sense of duty; let him even, in the pride of his fancied, and the ignorance of his true calling, bate no jot of his Jewish superiority; let him condescend to the very baseness of his own lowest nature; yet such will be the virtue of obeying an eternal truth even to his poor measure, of putting in actuality what he has not even seen in theory, of doing the truth even without believing it, that even if the truth does not after the deed give the faintest glimmer as truth in the man, he will yet be ages nearer the truth than before, for he will go on his way loving that Samaritan neighbour a little more than his Jewish dignity will justify. Nor will he question the reasonableness of so doing, although he may not care to spend any logic upon its support. How much more if he be a man who would love his neighbour if he could, will the higher condition unsought have been found in the action! For man is a whole; and so soon as he unites himself by obedient action, the truth that is in him makes itself known to him, shining from the new whole. For his action is his response to his maker’s design, his individual part in the creation of himself, his yielding to the All in all, to the tides of whose harmonious cosmoplastic life all his being thenceforward lies open for interpenetration and assimilation. When will once begins to aspire, it will soon find that action must precede feeling, that the man may know the foundation itself of feeling.

With those who recognize no authority as the ground of tentative action, a doubt, a suspicion of truth ought to be ground enough for putting it to the test.

The whole system of divine education as regards the relation of man and man, has for its end that a man should love his neighbour as himself. It is not a lesson that he can learn by itself, or a duty the obligation of which can be shown by argument, any more than the difference between right and wrong can be defined in other terms than their own. “But that difference,” it may be objected, “manifests itself of itself to every mind: it is self-evident; whereas the loving of one’s neighbour is not seen to be a primary truth; so far from it, that far the greater number of those who hope for an eternity of blessedness through him who taught it, do not really believe it to be a truth; believe, on the contrary, that the paramount obligation is to take care of one’s self at much risk of forgetting one’s neighbour.”

But the human race generally has got as far as the recognition of right and wrong; and therefore most men are born capable of making the distinction. The race has not yet lived long enough for its latest offspring to be born with the perception of the truth of love to the neighbour. It is to be seen by the present individual only after a long reception of and submission to the education of life. And once seen, it is believed.

The whole constitution of human society exists for the express end, I say, of teaching the two truths by which man lives, Love to God and Love to Man. I will say nothing more of the mysteries of the parental relation, because they belong to the teaching of the former truth, than that we come into the world as we do, to look up to the love over us, and see in it a symbol, poor and weak, yet the best we can have or receive of the divine love.

[Footnote: It might be expressed after a deeper and truer fashion by saying that, God making human affairs after his own thoughts, they are therefore such as to be the best teachers of love to him and love to our neighbour. This is an immeasurably nobler and truer manner of regarding them than as a scheme or plan invented by the divine intellect.]

And thousands more would find it easy to love God if they had not such miserable types of him in the self-seeking, impulse-driven, purposeless, faithless beings who are all they have for father and mother, and to whom their children are no dearer than her litter is to the unthinking dam. What I want to speak of now, with regard to the second great commandment, is the relation of brotherhood and sisterhood. Why does my brother come of the same father and mother? Why do I behold the helplessness and confidence of his infancy? Why is the infant laid on the knee of the child? Why do we grow up with the same nurture? Why do we behold the wonder of the sunset and the mystery of the growing moon together? Why do we share one bed, join in the same games, and attempt the same exploits? Why do we quarrel, vow revenge and silence and endless enmity, and, unable to resist the brotherhood within us, wind arm in arm and forget all within the hour? Is it not that Love may grow lord of all between him and me? Is it not that I may feel towards him what there are no words or forms of words to express– a love namely, in which the divine self rushes forth in utter self-forgetfulness to live in the contemplation of the brother–a love that is stronger than death,–glad and proud and satisfied? But if love stop there, what will be the result? Ruin to itself; loss of the brotherhood. He who loves not his brother for deeper reasons than those of a common parentage will cease to love him at all. The love that enlarges not its borders, that is not ever spreading and including, and deepening, will contract, shrivel, decay, die. I have had the sons of my mother that I may learn the universal brotherhood. For there is a bond between me and the most wretched liar that ever died for the murder he would not even confess, closer infinitely than that which springs only from having one father and mother. That we are the sons and the daughters of God born from his heart, the outcoming offspring of his love, is a bond closer than all other bonds in one. No man ever loved his own child aright who did not love him for his humanity, for his divinity, to the utter forgetting of his origin from himself. The son of my mother is indeed my brother by this greater and closer bond as well; but if I recognize that bond between him and me at all, I recognize it for my race. True, and thank God! the greater excludes not the less; it makes all the weaker bonds stronger and truer, nor forbids that where all are brothers, some should be those of our bosom. Still my brother according to the flesh is my first neighbour, that we may be very nigh to each other, whether we will or no, while our hearts are tender, and so may learn brotherhood. For our love to each other is but the throbbing of the heart of the great brotherhood, and could come only from the eternal Father, not from our parents. Then my second neighbour appears, and who is he? Whom I come in contact with soever. He with whom I have any transactions, any human dealings whatever. Not the man only with whom I dine; not the friend only with whom I share my thoughts; not the man only whom my compassion would lift from some slough; but the man who makes my clothes; the man who prints my book; the man who drives me in his cab; the man who begs from me in the street, to whom, it may be, for brotherhood’s sake, I must not give; yea, even the man who condescends to me. With all and each there is a chance of doing the part of a neighbour, if in no other way yet by speaking truly, acting justly, and thinking kindly. Even these deeds will help to that love which is born of righteousness. All true action clears the springs of right feeling, and lets their waters rise and flow. A man must not choose his neighbour; he must take the neighbour that God sends him. In him, whoever he be, lies, hidden or revealed, a beautiful brother. The neighbour is just the man who is next to you at the moment, the man with whom any business has brought you in contact.

Thus will love spread and spread in wider and stronger pulses till the whole human race will be to the man sacredly lovely. Drink-debased, vice-defeatured, pride-puffed, wealth-bollen, vanity-smeared, they will yet be brothers, yet be sisters, yet be God-born neighbours. Any rough-hewn semblance of humanity will at length be enough to move the man to reverence and affection. It is harder for some to learn thus than for others. There are whose first impulse is ever to repel and not to receive. But learn they may, and learn they must. Even these may grow in this grace until a countenance unknown will awake in them a yearning of affection rising to pain, because there is for it no expression, and they can only give the man to God and be still.

And now will come in all the arguments out of which the man tried in vain before to build a stair up to the sunny heights of love. “Ah brother! thou hast a soul like mine,” he will say. “Out of thine eyes thou lookest, and sights and sounds and odours visit thy soul as mine, with wonder and tender comforting. Thou too lovest the faces of thy neighbours. Thou art oppressed with thy sorrows, uplifted with thy joys. Perhaps thou knowest not so well as I, that a region of gladness surrounds all thy grief, of light all thy darkness, of peace all thy tumult. Oh, my brother! I will love thee. I cannot come very near thee: I will love thee the more. It may be thou dost not love thy neighbour; it may be thou thinkest only how to get from him, how to gain by him. How lonely then must thou be! how shut up in thy poverty-stricken room, with the bare walls of thy selfishness, and the hard couch of thy unsatisfaction! I will love thee the more. Thou shalt not be alone with thyself. Thou art not me; thou art another life–a second self; therefore I can, may, and will love thee.”

When once to a man the human face is the human face divine, and the hand of his neighbour is the hand of a brother, then will he understand what St Paul meant when he said, “I could wish that myself were accursed from Christ for my brethren.” But he will no longer understand those who, so far from feeling the love of their neighbour an essential of their being, expect to be set free from its law in the world to come. There, at least, for the glory of God, they may limit its expansive tendencies to the narrow circle of their heaven. On its battlements of safety, they will regard hell from afar, and say to each other, “Hark! Listen to their moans. But do not weep, for they are our neighbours no more.” St Paul would be wretched before the throne of God, if he thought there was one man beyond the pale of his mercy, and that as much for God’s glory as for the man’s sake. And what shall we say of the man Christ Jesus? Who, that loves his brother, would not, upheld by the love of Christ, and with a dim hope that in the far-off time there might be some help for him, arise from the company of the blessed, and walk down into the dismal regions of despair, to sit with the last, the only unredeemed, the Judas of his race, and be himself more blessed in the pains of hell, than in the glories of heaven? Who, in the midst of the golden harps and the white wings, knowing that one of his kind, one miserable brother in the old-world-time when men were taught to love their neighbour as themselves, was howling unheeded far below in the vaults of the creation, who, I say, would not feel that he must arise, that he had no choice, that, awful as it was, he must gird his loins, and go down into the smoke and the darkness and the fire, travelling the weary and fearful road into the far country to find his brother?–who, I mean, that had the mind of Christ, that had the love of the Father?

But it is a wild question. God is, and shall be, All in all. Father of our brothers and sisters! thou wilt not be less glorious than we, taught of Christ, are able to think thee. When thou goest into the wilderness to seek, thou wilt not come home until thou hast found. It is because we hope not for them in thee, not knowing thee, not knowing thy love, that we are so hard and so heartless to the brothers and sisters whom thou hast given us.

One word more: This love of our neighbour is the only door out of the dungeon of self, where we mope and mow, striking sparks, and rubbing phosphorescences out of the walls, and blowing our own breath in our own nostrils, instead of issuing to the fair sunlight of God, the sweet winds of the universe. The man thinks his consciousness is himself; whereas his life consisteth in the inbreathing of God, and the consciousness of the universe of truth. To have himself, to know himself, to enjoy himself, he calls life; whereas, if he would forget himself, tenfold would be his life in God and his neighbours. The region of man’s life is a spiritual region. God, his friends, his neighbours, his brothers all, is the wide world in which alone his spirit can find room. Himself is his dungeon. If he feels it not now, he will yet feel it one day–feel it as a living soul would feel being prisoned in a dead body, wrapped in sevenfold cerements, and buried in a stone-ribbed vault within the last ripple of the sound of the chanting people in the church above. His life is not in knowing that he lives, but in loving all forms of life. He is made for the All, for God, who is the All, is his life. And the essential joy of his life lies abroad in the liberty of the All. His delights, like those of the Ideal Wisdom, are with the sons of men. His health is in the body of which the Son of Man is the head. The whole region of life is open to him–nay, he must live in it or perish.

Nor thus shall a man lose the consciousness of well-being. Far deeper and more complete, God and his neighbour will flash it back upon him– pure as life. No more will he agonize “with sick assay” to generate it in the light of his own decadence. For he shall know the glory of his own being in the light of God and of his brother.

But he may have begun to love his neighbour, with the hope of ere long loving him as himself, and notwithstanding start back affrighted at yet another word of our Lord, seeming to be another law yet harder than the first, although in truth it is not another, for without obedience to it the former cannot be attained unto. He has not yet learned to love his neighbour as himself whose heart sinks within him at the word, I say unto you, Love your enemies.

THE END.